Lukas Jörg und Samuel Stehman sind zwei Mönche, wie sie unterschiedlicher kaum sein könnten. Beide haben wichtige Etappen ihres Lebens in der Dormitio verbracht.

60 Years an Adventurer

Clarion Herlad/New Orleans, October 21, 1976

By George Gurtner

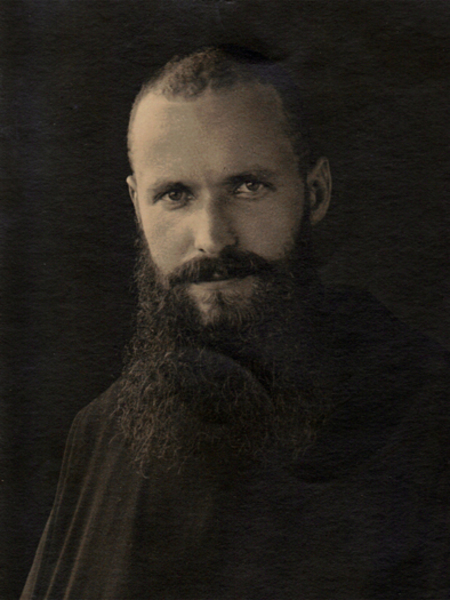

Lukas Jörg OSB in arabischer Tracht (ohne Jahr).

Father Francis Luke Joerg, O.S.B., talks with an enthusiasm about a past that belies his 85 years of the present.

Lukas Jörg OSB in arabischer Tracht (ohne Jahr).

Father Francis Luke Joerg, O.S.B., talks with an enthusiasm about a past that belies his 85 years of the present.

True, his once sprightly gait has been slowed greatly by arthritis and he doesn't find many occasions any more to use any of the seven foreign languages he speaks.

And, true, most of his days in “semiretirement” at St. Joseph Abbey are spent in reflection.

One year in jail

But mention Cairo, TransJordan, Jericho, any of the four citizenships he has held; or any of the thousands of points of adventure found by a young Father Luke, and he goes into motion.

“I was in Egypt, close to Alexandria at the end of World War I,” Father Luke remembers. “The British were in charge then and a full 10 days after the Armistice, they came along and threw me in jail because I was a German citizen. I spent one whole year there.”

“When I got out, I thought I would be smart. I said to myself ‘I’ll take out a Palestinian citizenship and get a British passport, then if war breaks out again, I am safe.’ Well, when World War II started, the British came immediately and wanted to put me in jail because I was a German.”

“I told them I am not a German. l am a Palestinian and I have here a passport issued by his majesty, King George of England. The British officer looked at me and said ‘That is nothing more than a scrap of paper, you are a damned German and you are going to jail.’ That time it was for eight months before the British realized they had made a mistake.”

A German with a Palestinian passport in Israel (1948)

Father Luke’s troubles with the British, however, ended when they pulled out of the Middle East and left the territory that was to become Israel in 1948.

What Father Luke didn’t realize at the time was that being a Palestinian citizen while living at a monastery in Jerusalem wasn’t the ideal situation either. Of course, his German name and heavy German accent didn’t help either.

Lukas Jörg OSB (1919, im äygptischen Lager Sidi Bischr).

“On May 15, 1948, the British left Palestine,” Father Luke says. “The high commissioner, the government, the military, the police. They all left. But immediately after they left, the Arabs and Jews started warring against each other.

Lukas Jörg OSB (1919, im äygptischen Lager Sidi Bischr).

“On May 15, 1948, the British left Palestine,” Father Luke says. “The high commissioner, the government, the military, the police. They all left. But immediately after they left, the Arabs and Jews started warring against each other.

“On the second day of the war, the Jews stormed the monastery I was in and put all the people there, about 20 of them, into jail, including me. I was a professor of Scripture there at the time and I could understand that the Jews would be against the Germans after what Hitler did, but they didn’t have to put everybody in jail.”

Escape – and Sentence of Death

Father Luke, who will celebrate his 60th jubilee as a Benedictine on Nov. 5, breaks into laughter when he tells how he outfoxed the Israeli guards and broke out of their desert jail in only three weeks: “One day a Red Cross representative came to the camp. We talked him into helping us escape.”

“There was a Red Cross jeep parked down by the gate, and we waited and waited for the guard to move on. When he did, we jumped into the jeep and took off. We drove down the road to a big house and what do you think we ran into: A Jewish patrol of about seven men all with machine guns. We told them were from the Red Cross and the house was our headquarters. They believed us.

“We didn’t even go into the house, we jumped over a garden wall and ran down into the valley and ran as fast as we could. As long as we were in the valley the patrol could not see us. But when we crossed the valley and went up the other side, they saw us and opened fire. Bullets were hitting all around us as we jumped from rock to rock and got farther out of range.”

“We ran up the hill and ran into ... an Arab legion. I thought they would shoot us, but they didn't they let us come near. I told them we were Germans and the Jews had put us in jail and we escaped. ‘You are our friends,’ I yelled to them.”

Father Luke made his way to Beirut where he became a hospital chaplain. lt was there that he learned that Radio Tel Aviv had issued a death warrant for him.

“That’s when I became a TransJordanian citizen,” Father Luke says with a sly grin. “It didn't take much more to convince me that it wouldn’t be too safe for me in Tel Aviv.”

America

Lukas Jörg (1957).

Next stop and next citizenship: America.

Lukas Jörg (1957).

Next stop and next citizenship: America.

Father Luke arrived at St. Ben in 1950 and immediately went to work waiting out the five year period that would allow him to become a citizen of the United States. “The first thing I did when I got American citizenship and passport was to go back to Israel. They had condemned me to death but I was sure nobody knew me anymore. Still I didn’t feel comfortable. What if somebody had recognized me and said there’s that priest, there’s that Father Luke who was condemned to death… I would have really been in a fix.”

That being the case, Tel Aviv odds makers would have made it even money that Father Francis Luke Joerg, O.S.B., would have dug into his bag of tricks and talked his way into working for the Israeli government

Father Stehman

(Einige biographische Notizen (auf deutsch) finden Sie hier.)

From: The Jerusalem Post Magazine, February 27, 1970

Shmuel Stehman (Foto aus der Zeitung).

There was standing room only at the Requiem Mass at the Dormition Abbey Church on Mount Zion on the evening of February 3, for Father Shmuel Stehman, the colourful Belgian Benedictine monk and lecturer who since 1957 had been Israel correspondent of the French Catholic daily La Croix, and who died suddenly the day before at the age of 58.

Shmuel Stehman (Foto aus der Zeitung).

There was standing room only at the Requiem Mass at the Dormition Abbey Church on Mount Zion on the evening of February 3, for Father Shmuel Stehman, the colourful Belgian Benedictine monk and lecturer who since 1957 had been Israel correspondent of the French Catholic daily La Croix, and who died suddenly the day before at the age of 58.

Dr. Jacques Lichtenstein

The significance of this large attendance is perhaps best explained by a quotation from a short and moving eulogy given after the ceremony of the Requiem Mass by Dr. Jacques Lichtenstein, the physician who had treated Father Stehman in his last brief illness:

It is I, a Jew, your brother, who is speaking to you from the Hill of Zion here in Jerusalem. Father Stehman – Shmuel to his intimates –had chosen to accompany the Jewish people in its renaissance on its ancestral soil.

Father Stehman was a man for confrontation: a priest who wished to live among the Jewish people; a man who, after being delivered from a concentration camp, chose to reside in a religious House whose language was German; a man of peace who yet chose to live every day on the frontier. He was a man for bringing people nearer together: a Jew for the Jews, a Catholic for the Christians. All of them considered him as a promise of reconciliation, perhaps even of forgiveness, between the two religions so long in conflict.

Father Stehman was a man of peace, one that continuously pursued peace.

Father Marcel Dubois

Another telling tribute was broadcast by Father Marcel Dubois, Superior of St. Isaiah House, on the same day on Kol Israel:

Father Shmuel Stehman was one of the personalities who was part of the Christian landscape of Jerusalem – or even more accurately the landscape of Jerusalem. It was in this city, with the consent of the Superiors of his monastery in Belgium, that he chose to live. In an autobiography admirable for its sagacity and humour (the book is soon to be published and through it we shall once more be able to discover him) he recounts his personal pilgrimage, and at the time of the Six Day War he gives us this admirable definition of a Jew:

A Jew is someone who weeps when the Shofar sounds before the Temple Wall.

Father Shmuel was one of those who wept on that June day, from the depth of his sense of belonging. Certainly this was more than sentiment in a man who had known so much uprooting and who had undergone the long winter of Buchenwald.

Each and every one of us who was acquainted with him was gladdened by him, though it is only the few who really knew him. There was no attempt on his part to conceal himself, yet there was Father Shmuel Stehman a genuine element of the mystic about him. He was many-sided: there was his gaiety and cheerfulness; the seriousness of a distinguished writer and artist; and yet again the air of detachment of a genuine monk. He was at all times possessed of a yearning, even of an obsession, for God.

In his book he recounts his presentation of himself at the Abbey. He told the Father Abbot who questioned him on his vocation: “I see no other way for me than the music hall of the monastery.”

All his life he Iived with this dual tension and attained a rare balance between smiling at the beauties of this world – for he was an artist of great talent – and the absolute of prayer, the balance between presence with men and solitude with God. In this regard there is a particular appropriateness in the day of his departure, the Feast of the Presentation in the Temple. This Feast suggests entrance into the Presence, the dominant theme and motivation in the life of Father Stehman.

Now his voice is silenced. It will no longer sound on Kol Israel or in the streets or houses of Jerusalem. But he has left us three beautiful books which, both by the quality of their writing and the revelation they offer us of his true self, will remain as a testimonial. We can hear him again in these lines of a book published some fifteen years ago called most appropriately ‘Le Voyage a l’Ancre’ .

Father Shmuel Stehman OSB

The life of man is a journey, the most perilous and the most secure, the most adventurous and the most circumscribed, a journey towards man, a Journey towards God, two unknowns without which we can know nothing.

My God, my God, I cannot be alone! I need to be two. My God, be this second, this other, this beloved, this loving one, life of my life, without which I am nothing!

You have enlarged my heart to the measure of the infinite, and it will remain empty, Lord, irremediably, as long as you will not come to fill it with yourself.